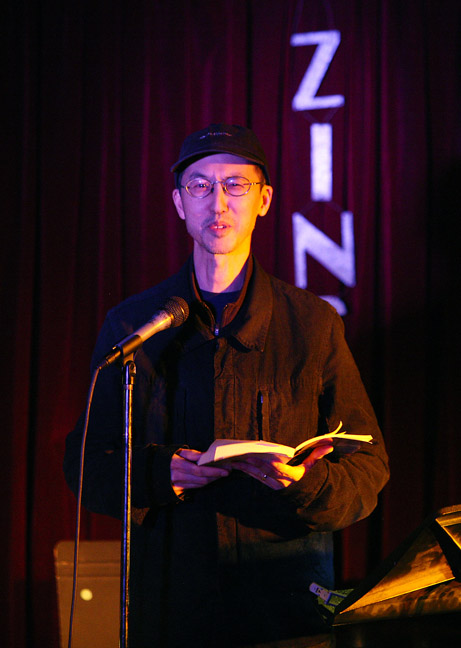

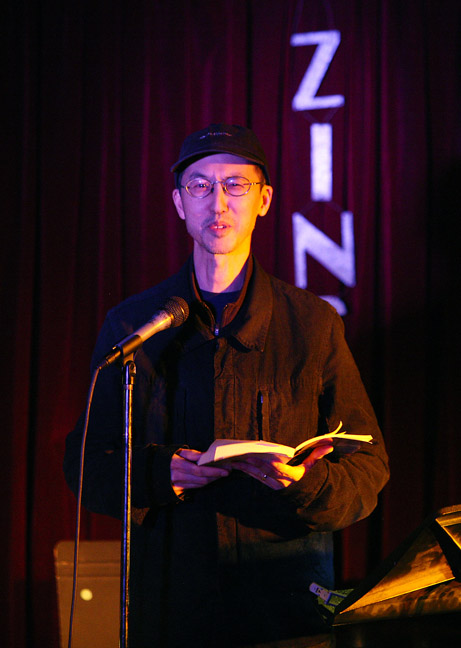

TAN LIN

ART IN AMERICA

6/11/10

It is within today's unsteady literary terrain that Tan Lin happily maintains his practice as a poet, essayist and artist. A remix of modernist poet Gertrude Stein's automatic writing, conceptual artist Douglas Huebler's self-reflexive appropriation of text and image, and cultural theorist Marshall Macluhan's analysis of media, Lin's works are as readable as they are relevant. Whether positing parallels between disco and Duchamp in his 2008 essay "Disco as an Operating System," or creating an "extended play" poem in his 300 page boring-on-purpose BlipSoak01, Lin's work engages with the present reality of interactive media, collective editing, and wholesale sampling.

Lin's latest book, Seven Controlled Vocabularies and Obituary 2004. The Joy of Cooking (Wesleyan Press) launched in April at the University of Pennsylvania's poetry department. There was no reading or signing. Instead, Lin worked with Editor and Archivist Danny Snelson to create an "editing event" titled Handmade book, PDF, lulu.com Appendix, Powerpoint, Kanban Board/Post-Its, Blurbs, Dual Language (Chinese/English) Edition, micro lecture, Selectric II interview, wine/cheese reception, Q&A (xerox) and a film. Students, professors, artists and writers convened at the Kelly Writers House, the poetry building of the University of Pennsylvania. The attendants were divided into groups and tasked with creating a series of supplementary texts and documents for Seven Controlled Vocabularies, which were then presented and discussed in a "micro lecture" at the end of the day. We began interviewing Lin at that event, and, in keeping with his practice, the process stretched onward...

ASHER PENN: When did you begin working on Seven Controlled Vocabularies...?

TAN LIN: It was completed between 2000 and 2002, and solicited by a small press, Faux Press. But the book was long and had a lot of pictures, so it was expensive to produce and the publisher asked me to pay part of the costs. At the time I thought that would be like self-publishing, and I declined. Of course I feel differently about self-publishing today, just as I do about Internet dating. Then I put [the book] away and kind of forgot about it.

So the book has a long pre-history, which I wanted to be a part of the book. I added the date 2004 and obituary to the title when I published it as a [self-published] lulu edition in 2004. Most books have a history of non-publication, but it's usually forgotten at the moment of publication. Any book has a lot of publication deaths in it, as they are revised or get a new cover; new photographs are inserted. All the WUP info, bar codes, ISBNs etc were finally issued and these became a part of the book's packaging—both its physical front cover and internal materials as well.

PENN: What were your models for the structure of this book?

LIN: I was writing a book on Warhol's books at the Getty. The Getty Library had developed a controlled vocabulary called the Object ID system for classifying objects in their collections. What is called a tabouret in France might be a "stool" in America, and the ObjectID system facilitated cross-institutional communication. I tried to apply this meta-data container to a literary work, and create a book addressing the idea that the lines between genres—architecture, novel, painting, poetry, etc.—have become increasingly less distinct, that we live in an era of standardized, even generic works where it is almost impossible to tell the difference between an experimental novel and a poem, or between an ad and an experimental film.

PENN: What does that make this book?

LIN: In a sense, SCV is a book as generic data object: at times it's like a painting and at others it's vaguely cinematic. It has a narrative structure, but it's loose like a tourist itinerary or inventory. I like it when I don't know what I am reading. Reading in this sense is just a theory on what T.S. Eliot called "the use of materials." When it came time to publish the book it was hard to figure out how Wesleyan, the publisher, should catalog it. Was it fiction? Literary criticism? Poetry? An artist's book in a poetry series? Fundamentally, I'd say the book is about generic reading practices, where reading is not just a linear textual experience, but an architectural container for impersonal texts and loosely correlated or near-random, unsearchable images.

PENN: What does this format produce, in terms of reading?

LIN: That's hard to say, but distracted skimming certainly. You put pictures and text in the same space. The minute you start reading text with images in it your attention is different, and SCV lays out some of these differences.

PENN: In your previous books it seemed like you were applying a specific technique for that individual title. Lotion Bullwhip Giraffe, while experimental in content, is formally cohesive as a book of poems. SCV reads like a compilation of literary approaches and themes.

LIN: I think you're right. Each of the earlier books was compiled according to a particular technique: machine-based language production in Lotion Bullwhip Giraffe, or relaxation, as in BlipSoak01, where I tried to create a work that would be deeply relaxing, like yoga or a disco groove. With SCV, there was a conceptual system: a compiling/cataloging system. I wanted a work that was both anecdotal and easy to read, a book that could read itself, as it were, or be read cover to cover in less time than it would take to watch a film. I was thinking of a book as it overlapped with other mediums, other timeframes and formats. SCV is a modular work with pictures in it. A book is a moving chronology of various events and people.

PENN: How did you decide how to organize SCV?

LIN: I laid it out in short pre-digested chapters, so that reading is not performed by an individual but something done for you, by bibliographic controls and modalities of reading such as architecture, landscape, cinema. Why read a book when it can be read for you? I think this is happening with ebooks: turning the page is a software command. Images and text inhabit the same, machine-searchable environment, although text and images get searched in often incompatible ways. Quite a bit of SCV doesn't quite fit; much of the content isn't immediately personal and most images were sampled from other sources. Body text functions as captions. Photos signify as key word searches "landscape," or "American painting." Likewise, vis-a-vis content, I often take stuff written by other people and loosely rewrite it as if it were mine—so there is sampling from and to other sources. Yet the book is old school analog, too. The landscape photos were, for example, purchased at the 26th Street flea market in New York. So is there a clear sense of an individual author responsible for material? Not really. There is a lot of digital to analog remediation. There seem to be multiple authors/software programs collectively writing something, but what exactly.

PENN: You make this explicit in your title, which is in fact three titles.

LIN: The question is: When does one book begin and another end? Why is that Joy of Cooking title in there? In some ways it was just a marketing ploy to increase Google hits. On another, it was the book my mother used to learn to cook American food when my parents moved to Athens, Ohio, from China in the 1950s.

PENN: What do you mean by the phrase "Controlled Vocabularies"? Who, in your imagination, is controlling the way these words are used?

LIN: In SCV these standards correspond roughly to the genres or subject headers of each section. A genre is a social agreement about how we use things, reading is a use pattern, and SCV is a bibliographic social agreement. But in the end it's a loose one and that's where a life, in my case a Chinese-American life centered on cookbooks and TV, among other things, falls into it. I suppose there's so much stuff about reality TV in the book because becoming American for my family was basically about watching TV, for my father NFL football, for my mother, Masterpiece Theatre, and for me and my sister, Gilligan's Island. SCV is about the most general contours of reading and remembering, and how specific books are connected to specific times of one's life. Since reading is, for me anyway, the chief process whereby things get into my memory, SCV is about how I remember my life. But there is not that much very personal information—much of that has been lost in this book. SCV's subject is the book as it lives ambiently connected to life. What is the life of a book in a post-book environment? How do we read it, and by read I mean run our retinas over it? And how do we preserve, organize and access it for future use?

PENN: Could you talk a little bit about the launch you did at the University of Pennsylvania recently?

LIN: The "edit" event was Danny [Snelson]'s idea and the nomenclature of the event—Edit: Rewriting Networks—touched on editing practices in a digital environment, which affects how we publish, republish, distribute and redistribute works. I aimed to use the event as an index of publishing. I didn't want a book to end with its publication but to begin there, be repurposed and remediated, transitioned from one published form to another. We don't have to accept a book anymore as something an author did but rather as something specific, personal and customizable to the reader. I really like Cliff's notes, indexes, PostIt notes, appendixes, critical readers—they enhance the book. It might be possible that these aids to reading will be more interesting than the book itself. Certainly editing a book is not a minor or dull practice: it's on a par with authoring. Why not customize a book in the same way that one customizes any number of design objects or sneakers? Benjamin Disraeil said when he wanted to read a good book, he wrote it. Today it might be more accurate to way when you want to read a good book, you edit it. Once a book enters a search engine, what the author meant isn't really very important anymore—it's what the book now means to the reader.

PENN: When I was there it felt more akin to a happening than a literary event of any kind. My memory of book launches seem fairly stagnant in comparison to the and fluidity that happened at UPENN.

LIN: The event was endless and ongoing like a happening; work wasn't completed at the event but is now transpiring in Wikis. It involved reading, writing, discussion, film, photography and graphic design. Even this interview got started at Kelly Writers house, while we were sitting outside and you were taping, but it's being finished up now, weeks after.

On June 24, Tan Lin will launch Seven Controlled Vocabularies and Obituary 2004. The Joy of Cookings at Printed Matter alongside the publications created at the previous launch at the University of Pennsylvania.